1

I discovered Etel Adnan1 at the Mori Art Museum on Christmas Eve in 2021. I hadn’t eaten all day, and I had no holiday plans though I wanted them badly. For Halloween I’d borrowed a friend’s blue suit jacket that he said he didn’t wear anymore because it was slightly broken. I put this on because it was still in my closet and went to Roppongi alone. I didn’t really know what kind of exhibition I was about to walk into, and I remember thinking this suit was the best thing I had—even though it wasn’t technically mine to have.

Once at the exhibition, I felt myself dissolve. The artwork was on display, not me, and I could just fold into nothingness as 16 women artists from around the world, whom I needed very much, told me what they meant.

Of Etel Adnan’s work, I first saw the paintings. I remember feeling like I had found something vital; an organ of some kind that had been misplaced. Rather, it felt like a small egg was hatching in my chest; opening, opening. There was a video interview playing on a loop in the room set aside for her. He made us feel that poetry was the basis of everything. She said from the television. I think I happened upon this section of the interview half a dozen times. It was only after I saw her hand-written and hand-drawn leporellos2 that I circled back and saw a small sign just below her name. It was the date of her passing: November 14th, 2021. Her biography remained unchanged and in the present-tense, it read:

Lives in Paris.

I felt the strange weight of this loss playing with the light-moving, recently hatched thing in my chest, and had tears about a person I didn’t know at all, but felt I’d just met.

2

Tokyo has no center. Said a New Acquaintance, taking a sip of his beer. The four of us New Acquaintances stood together in the corner of a small venue for live music in Daikanyama—post performance. We began to compare cities; the dimly lit room began to empty; people trickling onto the streets outside in search of a new focal point.

I wondered if Tokyo’s center, unlike other cities, was plural—stemming from its stations, small and large: Shibuya, Shinjuku, Kichijoji, Ueno, Shimokitazawa, Shinbashi, Koenji, etc. There are 882 stations in total, each one thriving within their own unique ecosystem and at varying degrees of busy-ness or tranquility. Seemingly self-sufficient, the neighborhoods are born of the trains we take to get there; many centers, many symbols inside them.

Paris, one of my New Acquaintances said, has a singular center space: Point Zéro. From here all the national roads are measured, and from here the city grows, as if Point Zéro is the seed. The nothing from which everything becomes something.

Roland Barthes3, author of Empire of Signs, wrote that Tokyo’s mysterious center was the Imperial Palace; an inaccessible place to the commoner, thus an absence. For Barthes, the metropolis of Tokyo was “a poem.” Japanese language, usually devoid of using the subject pronouns: I, he, she, they, it, we, you, lives inside verbs that just happen on their own. Sentences occur the way the streets do here: without names.

3

About a year and a half ago, I found myself in Bondi Cafe with a former partner. Things had ended badly between us. We’d decided to meet in order to mend some of the strings that had been severed. It was a windy day. We sat in couches that were angled towards one another at 90 degrees. The plastic sheet that separated us from the outside world rattled in the wind and the rain.

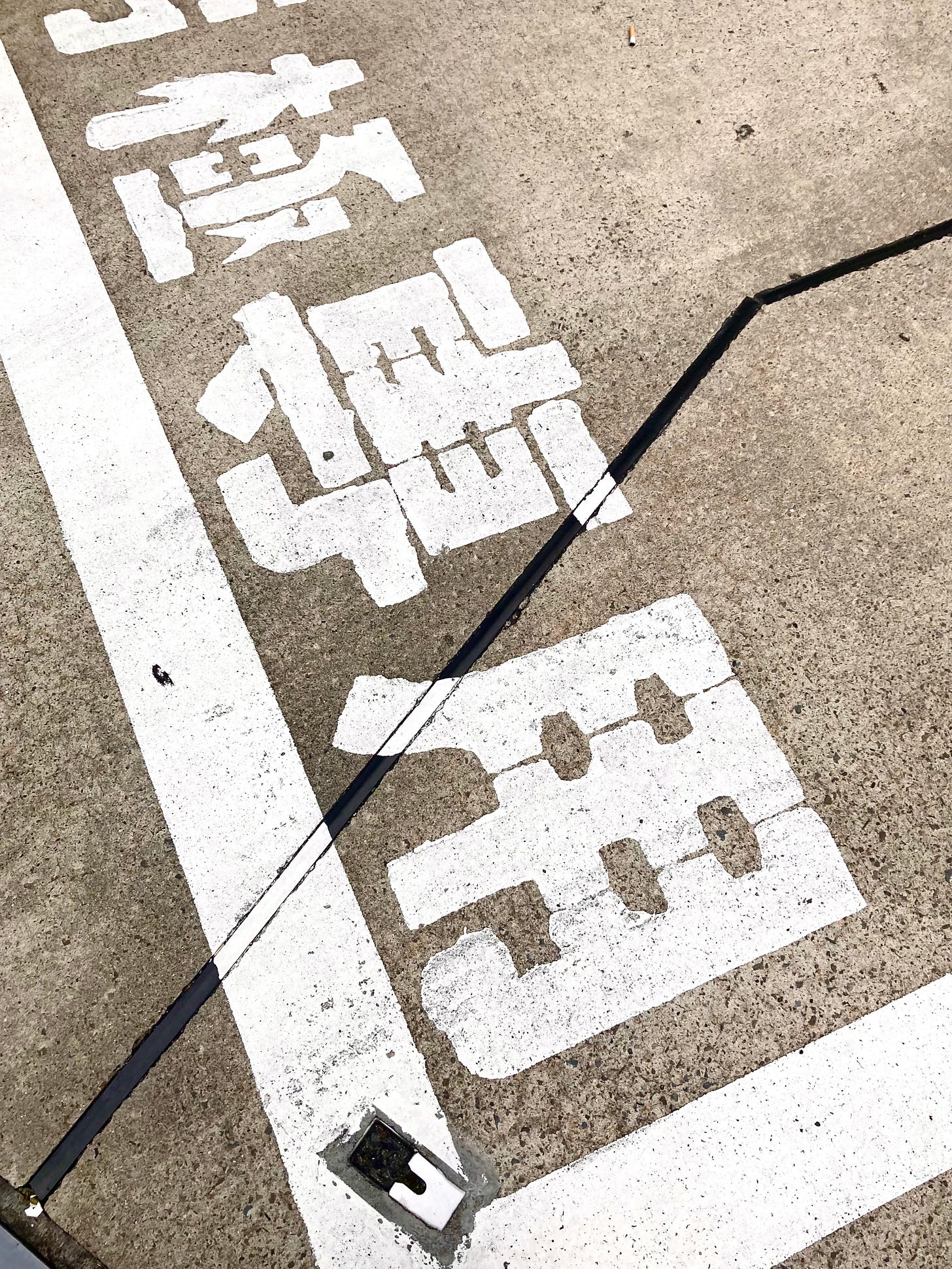

Not long after meeting, Bondi Cafe disappeared entirely. I remember walking by where it was supposed to be and believing I was looking incorrectly; maybe it was further down the road, further up the road—no, the cafe was now a parking lot. An empty space designed to be filled.

The parking lot has since disappeared. In its place, white walls have emerged, growing up and around the space and obscuring the whole of it from view. Just the other day I saw those white walls open like a curtain. Behind them stood a giant blue machine, digging up the ground with its claws. I was reminded of dinosaurs.

Adjacent to the late Bondi Cafe, sits a neighboring cafe known as Fuglen. Last week, my significant other and I met two architects there from Dubai. One of them mentioned Bondi Cafe, and how he missed it. He said he and his wife always used to go there when they landed in Tokyo; it was the only place open for coffee at 2am.

He asked me how long I’d been living here, then explained that he and his wife had made Japan a temporary place to visit on purpose. The hope was that not living here would sustain the city’s alchemy; keep Tokyo undiluted from the challenges of living.

On the benches outside Fuglen, the four of us spoke of cities, and the memories they hold. They asked me if I’d ever been to Beirut, a city my brother and I have long wished to go to—us children of mixed roots. They said: You must go. I must. I agreed. It turns out one of them had interviewed Etel Adnan years before. She was interviewing me more than I was interviewing her, he said with a smile.

3.5

Do the poetic layers of a place get lost from the chaos of living inside it? Who is to blame for losing it? I waver between laying blame on the city for chasing me with its troubles, and observing my own inner wiring; laying inquiries there, in my own movements that do not match my surroundings; my own movements that my surroundings do not match— But verbs just happen here, I note A sentence is more polite when it’s less direct, and happens on its own Without subject.

4

Tokyo deconstructs itself in painful, loud fragments. I was unaware of this at first. I used to walk its sidewalks adorned in construction sites believing the noise would end someday. I somehow trusted the friendly workers who smiled or appeared strained as they guided me away from the buildings being torn apart, pieces sometimes falling onto the pavement in protest.

But the revision is constant. Tokyo breathes laboriously, and without pause; morphing into something shiny and new and different—like a birth, but births come to an end, and Tokyo does not. I used to understand labor as a concept that was temporary, efficient, and rewarded. But I watch as this city collapses, then continues to extend itself further, passing thresholds, defining duration—there is no reward; no moment long enough to receive one. Meeting other people here can, at times, be equivalent to bumping into other bodies treading water, though some have perfected the ability of making drowning look like a pleasant swim. Others have found benefits here that arise from the advantage of time travel. They came for the dinosaurs hidden behind the curtains.

5

A Summary and Hanging-Conclusion: Maybe Tokyo Is Without Center—as New Acquaintances have said. Words like plural, and sprawling appear to make sense. Maybe Tokyo is not to be lived in because it is the thing that’s doing the living. To be in Tokyo, one must not fight against—but coexist with—the current, and to watch calmly as it eats itself. To detach from emotion as it removes itself of center, subject, fixed point—of anything that dares to define the nature of unfolding poems, broken borrowed suits, and buildings that get swallowed.

Tokyo is—

Tokyo is—

Tokyo is—

Lebanese-American Poet & Artist.

Scroll-like books/leaflets that unfold in a kind of accordion fashion.

French essayist & theorist, known especially for his work in semiotics: the study of signs and symbols. (Both visual and linguistic).

Jes would you ever do audio versions of your posts? I miss your voice and your podcast so badly.

I LOVE the way you weave in such a variety of topics and then manage to tie them all together at the end. Bravo!!!